How Are Holidays Created?

It turns out it takes a lot of lawmakers to make one happen (or just sending an email requesting one...).

Nov 14, 2023

Go ahead, crack open a cold one, or uncork a bottle of wine, and put your feet up. It's a holiday, right? You deserve it — especially since the holiday you're casually celebrating was probably a long time in the making and extremely hard won.

What is a holiday?

Although the word “holiday" derives from the term “holy day" and naturally first involved religious observances, the term is used broadly today and applies even to secular celebrations. (Some parts of the world use "holiday" to say they're taking a vacation!)

Religious holidays like Christmas, Easter, Passover, Rosh Hashanah, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, and Diwali are mostly self-explanatory. But America's secular ones — the list of which is ballooning — generally commemorate important people and historic events or raise awareness about critical issues.

They also fall under specific designations. Officially speaking, holidays in the United States include “federal holidays," “patriotic and national observances," and “recognitions" of specific periods of time (days, weeks, or months). Others that aren't sanctioned by religious institutions, or perhaps by any level of government, are lawfully designated as “celebrations," “appreciations," or “recognitions."

What's the difference and how do any of these days become a thing? Here's the rundown.

Federal holidays

Only Congress can designate federal holidays, which are established under the constitutionally prescribed voting process. These are sometimes referred to as “national holidays," but there's really nothing national about them.

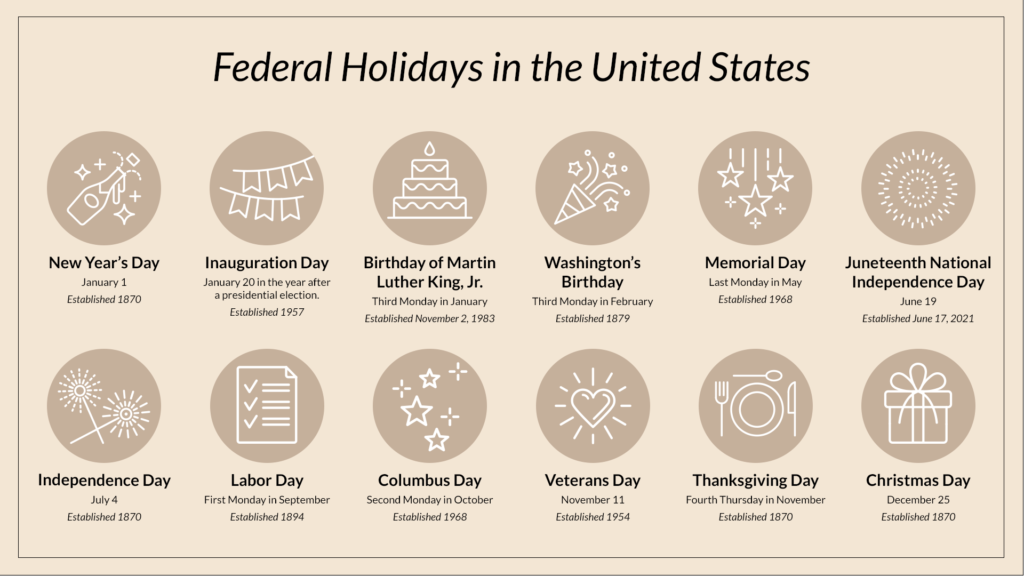

Individual states have the power to ignore federal holidays, and they've been doing so since 1870, when Congress approved the nation's first set of official holidays: New Year's Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day, and Christmas Day. In fact, states routinely opt out of holidays, and huge controversies have erupted over ones involving Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., Columbus Day, and Juneteenth.

States can even designate their own official holidays. For instance, Massachusetts celebrates Patriots' Day; Alaska celebrates Seward's Day; Louisiana celebrates Mardi Gras; Illinois and Missouri celebrate Malcolm X Day; California celebrates César Chávez Day; Rhode Island celebrates Victory Day; and several states celebrate Arbor Day (it's when you plant trees).

Nevertheless, the first four federal holidays were designated simply to exempt federal employees from work on such days. And even that exception originally applied only to the 5,300 federal workers in Washington, D.C., and not the other 50,600 stationed across the country. Not very democratic, right? This changed by 1885, and, as various states joined the party, people naturally began to think of these as “national holidays."

There are presently 12 legal federal holidays (see graphic). The fact that Congress has only approved a dozen over 247 years of our nation's history — and just four in the past 100 years —speaks volumes about how difficult it is to get D.C. lawmakers, of any era, to agree on anything, even holidays. You could chalk that up to federal holidays costing taxpayers more than $800 million per day off at last estimate, but it mainly has to do with the politically charged reasons our elected officials propose holidays, which don't often play well on the national stage. Thanksgiving, our nation's first and most original holiday, drives this point home. Although the Pilgrims first celebrated it in 1621, it took another 249 years — during which time there were some very heated debates, particularly between 1789 to 1870 — before the holiday became official.

Patriotic and national observances, and recognition periods

Like federal holidays, congressional statutory observances — known commonly as “patriotic and national observances" — can only be created by enacting laws. However, they differ from federal holidays in that they don't provide time off for federal employees.

Similarly, permanent recognitions periods (days, weeks or months) must be enacted by law. But temporary ones can be created after being introduced as resolutions by members of the Senate or House of Representatives.

The most widely celebrated of these days are Mother's Day, Indigenous Peoples Day, Flag Day, Patriot Day (9/11), Father's Day, Parents' Day, and National Grandparents Day.

Presidential proclamations

The U.S. Constitution does not specifically grant presidents the power to make proclamations — or, for that matter, executive orders. But that hasn't prevented them from issuing loads of both.

Proclamations are mostly ceremonial orders that sometimes result in laws and that often include “commemoration" days, weeks, or months. George Washington's first proclamation in 1789 honored Thanksgiving, and he repeated the act six years later. Lincoln also issued a Thanksgiving proclamation in 1863 — but none of these had the force of law. Recent examples range from George H.W. Bush's serious proclamation to honor veterans of World War II to Ronald Reagan's lighthearted and beloved National Ice Cream Month (July).

Presidents have also proclaimed holidays for the funerals of other presidents, most recently for Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Gerald Ford. But proclamations have most prominently been used to establish national heritage months, including Black History Month (February), Women's History Month (March), Irish American Heritage Month (March), Jewish American Heritage Month (May), LGBTQ+ Pride Month (June), Hispanic Latino Heritage Month (Sept. 15-Oct. 15), and Native American Heritage Month (November), among others.

Celebrations, appreciations, commercially driven observances, and “hashtag" holidays

The growing list of what we now commonly refer to as holidays are more technically designated as “celebrations," “appreciations," or “awareness" periods. Examples of those that are not religious in origin or federally backed include Groundhog Day (Feb. 2), April Fools' Day (April 1), Earth Day (April 22), Friendship Day (Aug. 7), Boss' Day (first working day nearest Oct. 16), and Administrative Professionals' Day (Wednesday of the last full week of April). The latter four of these originated in the U.S. and have become popular international observances.

Some popular holidays are purely commercially driven promotional opportunities that are sometimes referred to as “Hallmark holidays" or “shopping holidays." Specific commercial examples include 7-Eleven Day (7/11) and American Express' Small Business Saturday (Saturday after Thanksgiving). Broader-themed ones include Sweetest Day (third Saturday in October), Black Friday (Friday after Thanksgiving), Cyber Monday (Monday after Thanksgiving), and Giving Tuesday (Tuesday after Thanksgiving).

Some holidays are Hollywood creations that have captured the public's imagination and are either celebrated ironically, as is the case with The O.C.'s “Chrismukkah" (Dec. 10) and Seinfeld's “Festivus" (Dec. 23), or with explosive enthusiasm, such as Parks and Recreation's “Galentine's Day" (Feb. 13). The latter, a Valentine's Day alternative for women to celebrate their female friendships, has become so popular that it already has its own customs and growing selection of merchandise and greeting cards.

“Friendsgiving," which is a Thanksgiving meal celebrated among friends, is another example. Despite the popular myth, the compound word was never used in any of the memorable Thanksgiving episodes of Friends. It has been traced to a minor 2007 internet post but went mainstream in 2011 after it was used in a Bailey's Irish Cream campaign and an episode of The Real Housewives of New Jersey.

Then there are what's termed “hashtag holidays" — thousands of them, in fact, that are mostly internet driven and sustained annually using social media hashtags. There's literally something for everyone, appealing to all manner of passions and interests. A good deal of the well-recognized ones are known collectively as “geek days," the growing list of which includes Pi Day (3/14), Star Wars Day (May 4, as in “May the fourth be with you") and the accompanying next day “Revenge of the Fifth" (May 5, which is also Cinco de Mayo), Hobbit Day (Sept. 22), Star Trek Federation Day (Aug. 12), Batman Day (Sept. 16), and Fibonacci Day (11/23).

Not to be outdone by the intelligentsia, foodies have established a veritable smorgasbord of holidays dedicated to specific foods and their ethnic origins, beverages, diets, and even cooking traditions. Some of the most popular ones are National Wine Day (May 25), National Cheese Day (June 4), and National Chocolate Day (Oct. 28).

Are there any holidays we no longer celebrate?

Whether religious or secular in nature, holidays come and go, and that's true even for a nation as young as the United States. Many holidays that were celebrated in pre-colonial and colonial America were long forgotten by Lincoln's time. That's because Puritan religious holidays were intended as subdued days of solemn prayer, and the few remaining secular ones centered squarely on work.

That was intentional. Life was extremely difficult back then, in part due to the harsh winters, and a day off could very well threaten survival. Even Christmas and Easter were originally eschewed as potential distractions that could also invite ostentatiousness and encourage public drunkenness.

Instead, New Englanders eagerly celebrated harvest days, such as Sheep Shearing Day, Corn Husking Day, Maple Syrup Making Day, and Apple Peeling Day. One big holiday was Forefathers Day (Dec. 22), which honored those who risked their lives to travel to the New World on the Mayflower.

Virginia colonists especially enjoyed May Day (May 1), a spring celebration of nature's rebirth that involved erecting a tall pole, “the Maypole," which colonists decorated with flowers and danced around. Not to be forgotten was the three-day Christian celebration of All Hallows' Eve (Oct. 31) — Halloween by the 19th century — through All Saints' Day (Nov. 1) and All Souls' Day (Nov. 2).

Another well-celebrated holiday was Candlemas Day (Feb. 2), which involved a feast and the lighting of holy candles in prayer. But it became far more popular later on as the secular Groundhog Day thanks to English and German immigrants who began using the day to push a bit of folklore about the rodent's weather-forecasting abilities.

National Day Calendar: the internet's holiday gatekeeper

Keeping track of these special days, weeks, and months, and establishing thousands more, is largely the responsibility of the National Day Calendar, the popular website that is a kind of self-appointed arbiter of fun days.

For decades, that duty had been the sole province of Chase's Calendar of Events, the stately chronicler of more than 10,500 special occasions whose annual reference volume remains a staple of newsrooms everywhere. But beginning around 2017, just four years after the National Day Calendar was established, the team brought holiday making into the digital age, taking full advantage of the world wide web and social media to push the company's cheerful mission (and motto) to “Celebrate Every Day."

“We spread positivity around the world and take pride in the fact we put smiles on people's faces every day," says company CEO Amy Monette. That's not just a marketing ploy. She and her small team of “event makers" are practically giddy about putting new celebrations on the calendar — roughly 1,700 "National Days" on the calendar and close to 3,500 overall days, weeks, and months, which are designated “National Days."

Anyone can propose a holiday at the National Day Calendar. In fact, the staff receives thousands of proposals each month, and it's committed to reviewing and responding to every one. Competition is extremely stiff. Only about 30 to 35 holidays are approved each year — up from 25 a few years ago — and that only happens by way of a unanimous vote from a four-member committee.

“What we consider a 'good' submission varies and depends on the topic," Monette says. “There are fun topics, serious topics, informative topics, iconic topics, and so forth. However, I think all of us subconsciously think about whether something is unique, will trend well on social media, and has an important message."

Politics is a definite no-no, as is “anything that could be considered offensive or harmful if celebrated," Monette explains. Brand-specific days, such as National Starbucks Day, are non-starters; National Coffee Day (Sept. 29), however, not only gives coffee lovers an extra reason to imbibe and get together but also provides coffee sellers with an annual promotional opportunity. You're certainly welcome to propose a celebration day to honor your amazing brother or sister, but it wouldn't fly — National Siblings Day (April 10) already serves that purpose.

So, which days are Monette's favorites? The chief celebrations officer confesses to being particularly fond of National Sangria Day (Dec. 20) and National Pizza Day (Feb. 9), the latter of which she considers a “food group." But her secret passion seems to be National Talk Like a Pirate Day (Sept. 19), which improbably captured the public's imagination ever since its launch in 1995. “I wanted to be a pirate and hunt for treasures when I was a kid," Monette says, laughing. “Talk Like a Pirate Day makes me giggle and reminds me of how lucky I am not to have chosen that career path."